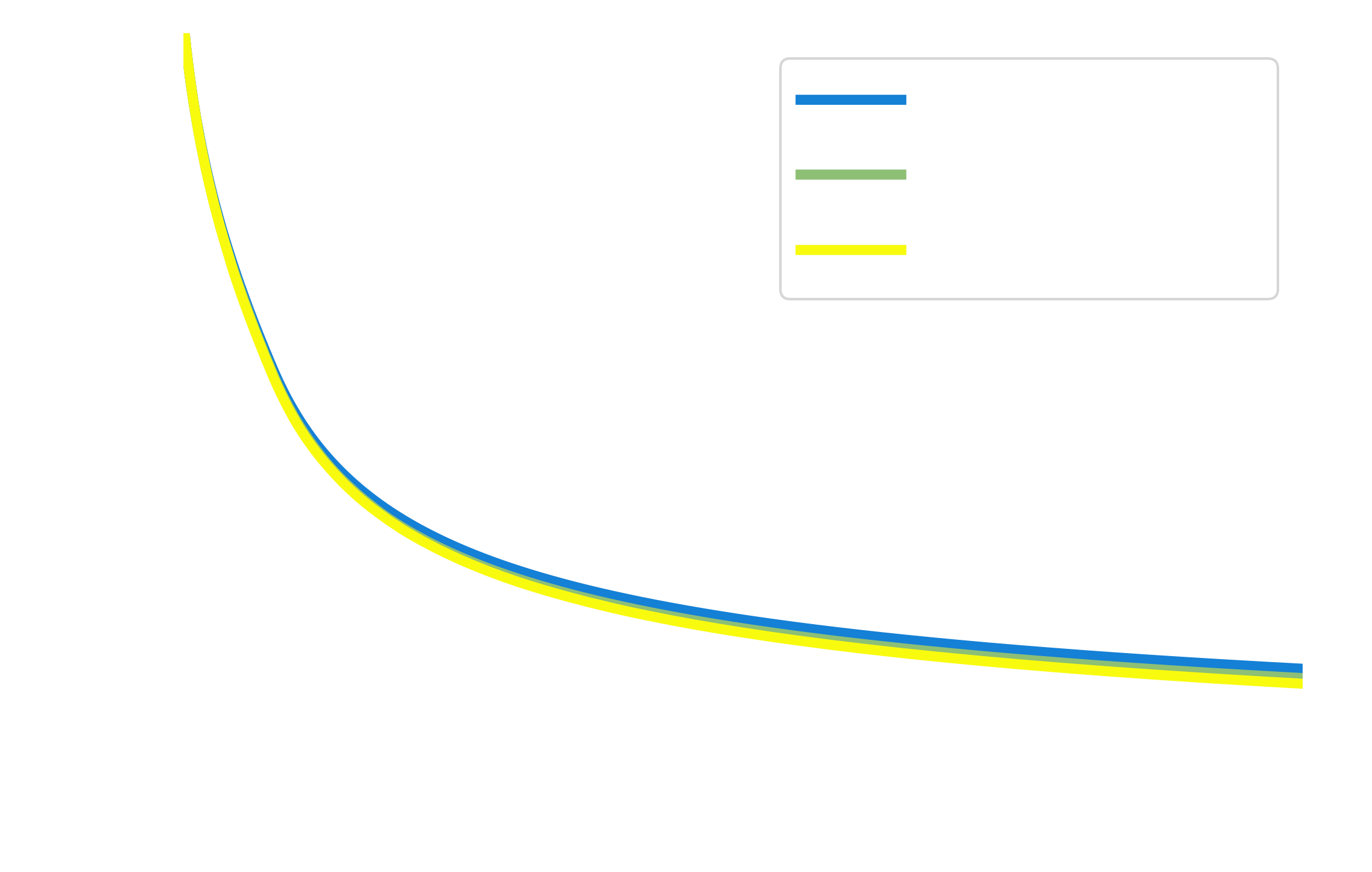

Modifying the photoevaporative atmospheric mass loss equation from

Owen & Wu (2017),

to account for flares, we find that:

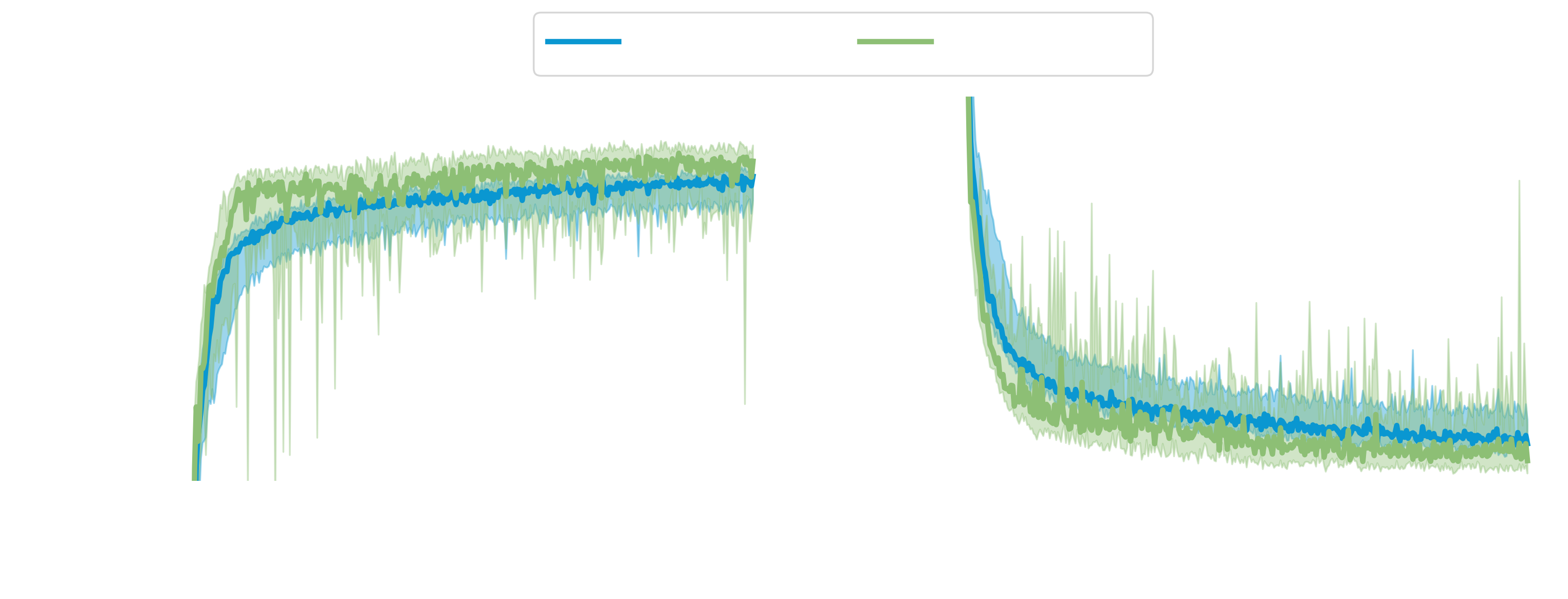

- When flares are present for the first 200 Myr, 4% more atmospheric mass is lost (green curve).

- When flares are present for the first 1000 Myr, 7% more atmospheric mass is lost (yellow curve).

Although these differences when accounting for flares do not seem large, this does suggest that flares need to

be accounted for in more detail moving forward.

Flares have been shown to alter atmospheric chemistry. Here, we demonstrate they could partially affect mass-loss rates during formation.